Itchy, knee, san? Japanese 101: numbers

Out of all the Japanese words that I know, I don't think I will ever forget 1, 2, 3 in Japanese. Why is that you ask?

Out of all the Japanese words that I know, I don't think I will ever forget 1, 2, 3 in Japanese. Why is that you ask? Because about 2 years I was told of a way of remembering Japanese numbers with actions although, I only remembered actions for 1 to 3. 1. いち (Ichi)一 2. に (ni)二 3. さん (san)三 or itchy, knee, san. I practised it so much that I subconsciously itch my arm when I say ichi, then I will practise the other ones by pointing at one of my knees and then my nose as that's how the Japanese gesture towards themselves. Also, San is an honorific that is a title of respect which would be added to a surname or a given name like Ben-san and that's why I point at my nose.

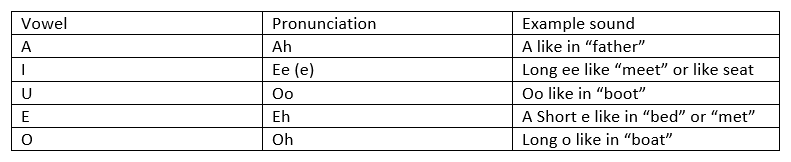

While I was writing this, I realised that I need to help everyone over a small hurdle, vowels! You might have already noticed this with ni (2) as all you must do to say that is say knee. But I emphasize the e when saying it. So, let's do a quick look over the 5 vowels.

But do not worry about vowels too much as I will do a post talking about vowels in more depth.

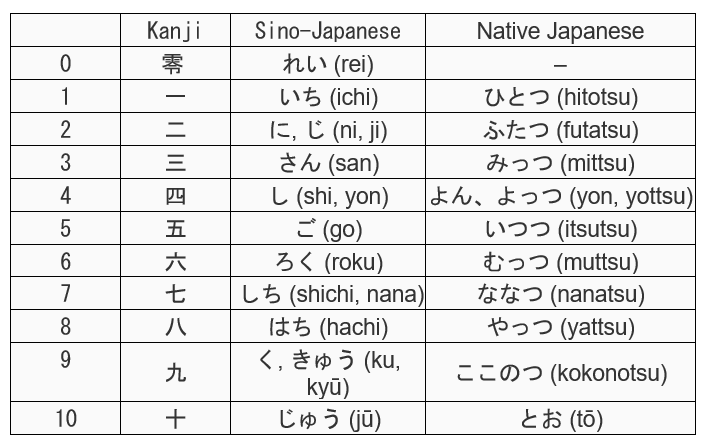

In Japanese, there are two number system, Native Japanese and Sino-Japanese numbers. Sino-Japanese is the common system used in day to day but Native Japanese is a universal system which only goes up to 10. Truth to be told, I have never used the Native Japanese system unless it's in writing which is easy to remember as all but 10 have tsu (つ ) at the end.

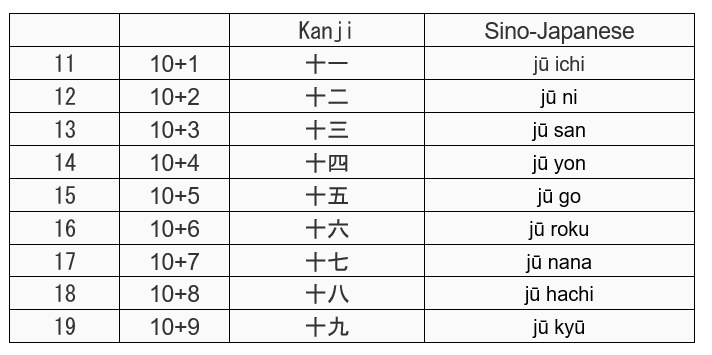

So how does one count from 11 to 99? Well, the trick is to learn the 1-10. When you get those numbers down, the rest is easy as all you must do is add. So, let's start with 11-19:

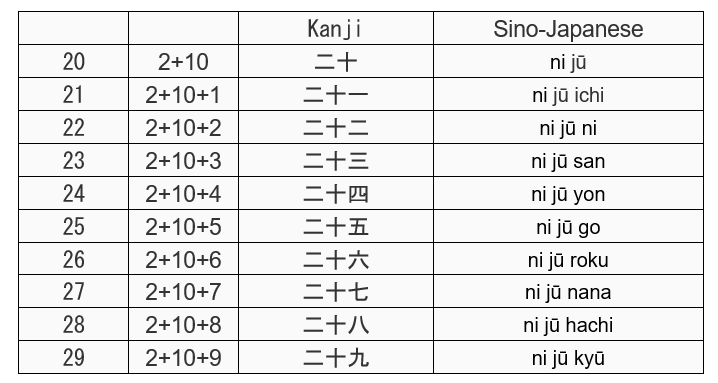

As you can see, the formula is 10 + 1 to 9 so you start with jū and then add the next number. But what happens when you need to say 20 or 21 or 27.

Now you can see a pattern forming, so let's look at the improved formula again: 1-9 + 10 + 1-9. So, to write 20 is ni jū, what about 30? san jū. 47? yon jū nana. 99? Hachi jū hachi.

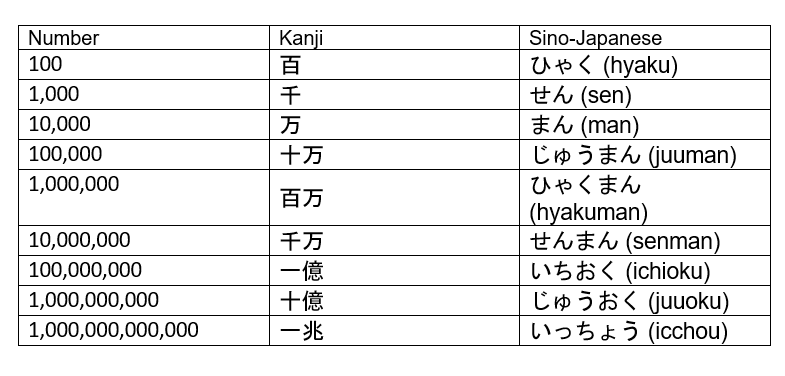

So, what about 100? A new word. yet this is where I say the number becomes more valuable, not in the sense of being a high value but in terms of the use of the numbers. 100 yen is not a lot, as I imagine it as £1 (although it actually is £0.72 currently). So, 1,000, 10,000, 100,000, etc are used a lot when talking about prices for things.

To be fair, you probably only need to know up to senman if you are only visiting because if you are buying something more than 10,000,000 then please message me to tell me what you are buying. So, let's take a random number and break it down into the formula. For example, 4677 which is 四千六百七十七 .

So, let's start by breaking down the kanji into their separate numbers one by one.

· 4 = 四

· 1,000 = 千

· 6 = 六

· 100 = 百

· 7 = 七

· 10 = 十

· 7 = 七

So, let's now group them up: 四千, 六百, 七十七. You should know 七十七 is 77 if you went through the formula all the way to 99. 四千 is 4000, and 六百 is 600 so if we pop 4000, 600, and 77 into the formula, you get 4677.

Counting other things than coins:

When it comes to talk about the number of people in a group, Native Japanese numbers comes into play in the case when you are talking about one person (一人), or two people (二人). After two people, Sino-Japanese numbers are used again.

What about if you want to ask the person behind the till what day it is? Well most of the dates use the Sino-Japanese number system but like the people in a group, there are irregularities. Most days are formed by saying the Sino-Japanese number and nichi (日) which is day (we will talk about this again in the future so keep your eye on that post) As July the 31th has just passed, let's use that as an example, using that formula I was using earlier, we can work out 31 as san x jû x ichi which equals sanjûichi. So, to make it into a day, we add nichi so now we have sanjûichi-nichi. So, what days don't use Sino-Japanese? 1-10th, 14th, 20th, 24th.

Japanese number superstitions

I have one last thing to talk about before I close off this blog for this week. As I been going through the numbers, you might have noticed an occurring pattern with some of the numbers e.g. 4, but why is that? Well 4 and 9 sounds very similar to “death” and “suffering”. These superstitions are a big part of their culture, throughout my trips I have noticed these numbers are missing as such. How could these numbers be missing??? For example, sometimes hotels won't have hotel rooms with the numbers: 4,9,44,49,99, or they won't have a fourth floor.

But do not worry, it isn't all dark and gloomy. There are numbers that are lucky. 7 is probably the most well-known lucky number in Japanese culture. 7 is seen as a very lucky number as there is the Seven Gods of Luck (Shichifukuin - 七福神): Ebisu, Daikoku, Benten, Fukurokuju, Hotei, Jurojin, Bishamon.

There is also the seven virtues of bushido code:

- Justice or Rectitude (義 gi)

- Courage (勇 yū)

- Benevolence or Mercy (仁 jin)

- Respect (禮 rei)

- Honesty (誠 makoto)

- Honour (名誉 meiyo)

- Loyalty (忠義 chūgi)

Plus, with Buddhism, being the main religion of Japan, there is the belief of seven reincarnations. And this is only the beginning, Tanabata (七夕) which is the evening of the seventh is seen as an important summertime holiday which is celebrated on July 7th as traditions around birth and death are pivot around 7. A baby's birth is celebrated on the seventh day, a death is mourned for seven days, and again after seven weeks. Therefore 7 is seen quite often in pachinko parlours and on scratch tickets where luck is needed.

8 is another lucky number as it is said to bring prosperity. It's kanji, 八 said to widen at the bottom to bring in more luck and success. Some people mention how the kanji reminds them of Mount Fuji, which is considered to be a lucky mountain to the point where it is said that dreaming of Mount Fuji on New Year's night will bring luck.

Conclusion:

This post was always going to have to be one of the first ones I did as Japanese numbers was the first thing I learnt apart from greetings. Even though, greetings would have seemed like the better option for the first Japanese 101 blog, Japanese numbers are a good example of how their vowels sound and used. So, it's time to say a big thank you to everyone reading this week's blog. In terms of next week, it will be on Japanese traffic lights and pedestrian crossings, where I will talk about fun facts about them. The next blog is the start of building sights, sounds, and feels of what I experience as I travel around Tokyo and Japan. So, until next week, arigatou gozaimasu and sayōnara!